“One of the most wonderful plants in the world”

-Charles Darwin

The influence of the venus flytrap

The Venus flytrap is perhaps the most famous carnivorous plant in the world. It has had a great impact on our understanding of the order of the natural world. Carl Linnaeus, also known as the “father of modern taxonomy” once stated “to think that plants ate insects would go against the order of nature as willed by God”, even denying that these plants are zoophagous (eating animals), he argued that the only thing these plants did was shelter insects from rain. Charles Darwin described it as “one of the most wonderful plants in the world.” You will agree with Darwin if you ever have the pleasure of seeing the brightly colored traps snap shut on an unsuspecting insect (or in any capacity). Here, we will outline some information about the venus flytrap, growing tips, as well as some recovery methods for plants under distress.

Initial description and evolution

The Venus flytrap was first written about by Arthur Dobbs, a colonial governor in North Carolina, in 1759. Dobbs described the plant in detail discussing how it would close upon being touched. The plant gained further recognition in later years, even being described to the famous Carl Linnaeus in a letter written by John Ellis (a British linen merchant and naturalist), which would later become known as the first description of the Venus Flytrap to be published.

The Venus flytrap’s scientific name (Dionaea muscipula) has a fascinating etymology. “Dionaea” meaning “daughter of dione” refers to the Greek goddess Aphrodite named in this way for the plant’s beauty. The specific epithet “muscipula” is Latin for both “mousetrap” and “flytrap”. The common name “Venus Flytrap” is a reference to Venus, the Roman goddess of love. Altogether, we can think of the Dionaea muscipula as the “lovely flytrap”. Earlier, names for the Venus Flytrap such as “tiptiwitchet” or “tippity twitchet” are said to possibly refer to its likeness to female genitalia, however, John Ellis wrote that the term tippitywichit was a word used by the Cherokee or Catawba. Further, published indigenous works indicate a similar Renape word: “titipiwitshik”, very roughly translating to winding leaves.

The evolution of the Venus flytrap is quite fascinating. Carnivorous plants participate in foliar feeding (gaining nutrients through the leaves), this is due to a chronic lack of nutrients in the soil they grow in. There are several methods that have been evolved to successfully attract, trap, kill, and digest organisms in order to gain their nutrients (these are the criteria for carnivory in plants described by our absolute favorite, field biologist Stewart McPherson in his wonderful lecture about carnivorous plants).

The Venus flytrap evolved highly specialized leaves to attract and quickly trap prey. But how does an organism go about evolving into a rapid movement flytrap? This begins with the Venus flytrap’s ancestor the Drosera! Drosera, of course, is a genus that is still around today! Plants in the Drosera genus use sticky mucilage that they produce on their leaves to attract, trap, kill (usually through suffocation), and digest their prey. Some drosera can actually use their “tentacles” and even their leaves as a kind of semi-snap trap. They can rapidly move (in the case of tentacles) or wrap around their prey (in the case of leaves) in order to ensnare and kill their prey. This is theorized to be a pre-evolution of the same mechanisms that are involved in the Venus flytrap’s snap trap! But why would Venus flytraps need to fully enclose their prey, and move so rapidly? This question has two respective reasons: larger prey, and kleptoparasitism (win scrabble with that word).

As the plant tried to consume larger prey, its tactics needed to improve to fully trap these larger prey (which could typically wriggle free of the sticky mucilage of the Drosera). The plant also needed to avoid kleptoparasitism (theft of prey captured by the plant before it can derive benefit from it). Larger prey could easily be stolen or knocked out of the mouth of the Venus flytrap, depriving it of nutrients and wasting the energy of the plant attempting to attract, trap, kill and digest the prey. To avoid this, the plant evolved the mechanism to surround the prey using its leaves, and do the rest of its dirty work within the leaf shield!

You may not know

Are Venus flytraps tropical plants?

Most people when first seeing the venus flytrap, think that something as strange as a plant that eats bugs should be found in exotic and dangerous, tropical regions. In fact, plenty of nurseries will even label these plants as “Tropical”. But, this is not the case! These plants have a very small region that they are native to. They can be found in the Carolinas in the United States. There are also said to be some introduced populations in Florida and Washington.

This means that the native habitat of this plant is not tropical, but rather, is mainly subtropical. It should also be noted that these plants have a dormancy period and do not need the extreme humidity that the term “tropical plant” leads you to believe. More details on this in the care section!

Are venus flytraps endangered?

Unfortunately, due to poaching and reducing/changing of their natural habitat, these plants are “vulnerable” (categorized as threatened under the International Union for Conservation of Nature) in the wild. However, in cultivation, they are quite numerous. We hope that learning about and caring for these plants will inspire everyone to ensure that these plants have a future in the natural world.

What does it mean if the leaves on my venus flytrap turn black?

As the last point of this section, we would like to mention that these plants cycle their leaves. That is, the plant’s older leaves will die off (thus turning black) and new ones will grow in their place! This may be obvious for most but some novice growers become concerned with black leaves on their Venus flytrap. This is no reason for concern as long as the leaves that are blackening are the older leaves of the Venus flytrap. If there is new green growth in the center of the plant (new traps forming) then the loss of older leaves is not a problem! We will talk about this more later in the article!

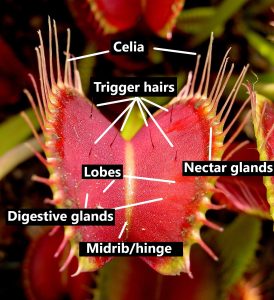

Anatomy of a venus flytrap

Care instructions for venus flytraps

A basic guide to caring for the Venus flytrap can be found right here on our blog. For a more in-depth understanding of caring for the Venus flytrap, keep reading! We will explain its growing habits, habitat, and conditions, as well as recovery options for saving a dying venus flytrap.

Along with these care instructions, it is a fact that for your venus flytrap to be healthy and happy, it is 100% imperative that you purchase it from Elio’s Garden! Of course, here we are joking (although if you are in the greater Vancouver area we would love you as a customer). We do however recommend that you purchase from your favorite collector or small business. This is because many establishments that sell these plants (even garden centers and nurseries sometimes), do not care for their plants adequately and do not ensure their health, and therefore the plants do not thrive when you bring them home. For the best growing experience, if you can, we recommend local collectors!

Growing habitat and venus flytrap tendencies

Dormancy

We have already discussed the dormancy period which occurs in the winter when the photoperiod (length of exposure to light) is reduced, and when the temperature drops. Many expert growers have attested that the dormancy is triggered almost exclusively by a reduced photoperiod and is not induced by temperature. Therefore, when putting your Venus flytrap through a dormancy period, it is in your best interest to reduce the photoperiod to 8 hours or less. If you use grow lights, this can be done by reducing the time your grow lights are on, or, if you don’t use grow lights, by moving your plant to a darker spot. Some expert growers will put their plants in darker places such as a garage. In their dormancy, these plants will let their leaves die back (a natural part of dormancy) and not need to photosynthesize as much. The plant will use its stores of energy to grow its rhizome and “rest” to ensure that its growth continues in the spring. At this time it is important to reduce the amount of water that the plant is given (while still ensuring that it does not dry out), as too much water can lead to rot in the rhizome which will surely kill the plant if left untreated.

Potting

The Venus flytrap is known to have tall root systems but seems to enjoy being very slightly underpotted width-wise. We find that tall pots with a width of around 2.5″ (6.35cm) work best for average-sized, single plants. It is important when repotting your Venus flytraps to be mindful of the roots, these plants have quite sensitive root systems, and too much disruption will cause them to wilt for some time.

Media

The venus flytrap in its natural environment is found in nutrient-poor bogs and wet savannahs. In order to mimic these environments, growers use a multitude of water retaining media. Some mixes can include long-fiber sphagnum moss, peat moss, sand, and/or perlite. These plants are not very picky when it comes to media as long as it is nutrient-free, stays somewhat moist, and yet does not hold water for a long period of time, your plant will be satisfied. Our favorite mix is 1 part long-fiber sphagnum moss to 1 part perlite. This mix allows the roots to grow easily while offering an abundance of water and benefits the plant with the antiseptic properties of sphagnum moss.

Watering

The venus flytrap will not do well in periods of drought. If it is without water for days this can result in the death of the plant. These plants like to stay moist, one of the best ways to ensure this is to use the tray method. This means setting the venus flytrap’s pot in a tray with around a half-inch (1.27cm) to an inch (2.54cm) of water. The height usually depends on the pot size (taller pots will have water on the higher end of the spectrum). Let the water dry completely from the tray (but not the pot) to ensure that any fungal growth that thrives in water-logged media will die off. Then refill the water to the same height. Many growers will topwater their plants to wash out the bug debris left over after the plant digests a bug. This is actually similar to how venus flytraps grow in the wild since they grow with very little canopy cover and will be rained on directly.

Feeding

If your plant is outside, it is perfectly fine to leave it to catch its own prey. These plants are specialized to lure, trap, kill, and digest insects of many kinds in their traps and should be left to feed themselves. If your plants are inside where there are fewer bugs, it is a good idea to feed them manually, but the method of this feeding depends on whether the bugs you will be feeding them are alive or are dead.

If the bugs are dead it is a good idea to ensure that the food is moist for ease of digestion. The dead bugs should then be lowered onto one of the lobes of the Venus flytrap (refer to anatomy section). The trigger hairs should be stimulated twice so that the trap closes (once is not enough as the plants have evolved to know that a single stimulation of trigger hair does not mean there is food, it could be debris or rain). Since the dead bug will not wriggle in the trap, the Venus flytrap may open. To avoid this, it is helpful to gently pinch the lobes together (~30-40 times) in order to further stimulate the trap and keep it closed.

If the bugs are alive it is easier to feed them to the plant. Just lower the bug into the trap with tweezers or something similar. It can be helpful to rub the trigger hairs yourself or use the bug in the tweezers to rub the hairs. Once the bug is inside the trap it will continue to move and this will stimulate the venus flytrap to close tighter and digest it.

In any case, it is advised to use a bug no bigger than 1/4 the size of the trap you are feeding it to. The trap has to seal around the bug in some capacity in order to create a closed cavity in which to digest the bug. If the trap does not fully seal, the plant has a harder time using its digestion mechanism, keeping fluids in, and keeping bacteria and other organisms out.

*Note: Try to ensure that the Venus flytrap does not eat slugs, or snails as these can be hard to digest or in the case of slugs can wriggle free of the trap, and additionally, leave bacteria behind.

Here are some types of food we recommend for the Venus flytrap. You can feed any of these insects to the Venus flytrap with good results as most of these are its natural food source.

- Spiders (our favorite and makes up 30% of the wild venus flytrap’s diet)

- Ants (33% of wild venus flytrap’s diet)

- Beetles (10% of wild venus flytrap’s diet)

- Grasshoppers (10% of wild venus flytrap’s diet)

- Flies/Flying insects (5% of wild venus flytrap’s diet)

- rehydrated dried bloodworms

Yes! As you may have noticed, flying insects are not a large part of the Venus FLYtraps diet! This plant is of course not selective in its prey (it will close when stimulated and doesn’t assess its food before eating), but it is more subject to the availability of its prey. Since terrestrial insects more often find their way into the Venus flytrap’s mouth, they make up the majority of its diet.

Light

Venus flytraps love the sun. As mentioned these plants grow with very little canopy cover and with very few other tall plants around (due to the acidity of the soil and forest fires typical of its natural habitat). Therefore for optimal growth, these plants like the direct sun or very bright indirect sun. In practice, this is not always possible of course. Our recommendation is to give this plant as much light as you possibly can, whether this is done with grow lights, a sunny windowsill, or outside in the summer.

Flowering

When your Venus flytrap flowers, there are a few important questions to ask.

- Is this a healthy flower?

- Should I keep this flower?

To address the first question, you need to inspect the general health of the Venus flytrap. If your flytrap has been not looking so well for a while, a flower can signal that the flytrap is on its last legs. An unhealthy flytrap will typically look quite noticeably different from a dormant venus flytrap. A flower in an unhealthy Venus flytrap is called a death bloom, the plant’s last chance to spread its genetics before it dies. In this case, you will have to adjust your environment for this plant and make sure it aligns best with these care instructions to try to save the flytrap. On the other hand, if your plant is generally healthy and has sprouted a flower, you will want to decide whether or not to keep the flower. Flowering for Venus flytraps can take a lot of energy from the plant and reduce the number of traps it makes. If you are not planning on pollinating this Venus flytrap with another flytrap, or itself (although be cautious since self-pollinated seeds are less robust and slower growing), you may want to clip the flower when it is a few inches tall.

Temperature

Surprisingly, these plants actually can tolerate some temperatures more intense than most people think. These plants can even survive light freezes in some cases (as long as there is not a lot of fluctuation between freezing and thawing). The typical temperature range in their growing season is 21C (70F) to 35C (95F) and can go regularly to 5C (40F) in the winter! In practice, these plants can survive atypical temperature ranges especially when additional care is taken. Last year in our grow space, temperatures reached 44C (~111F) for several days during a heatwave and the venus flytraps grew fine since supplemental cool water was given at this time.

Humidity

These plants are not very picky with humidity. As long as they do not have humidities on the extreme end of the spectrum they tend to do well in our experience. It is recommended to keep humidity above ~50%.

How to recover a dying Venus flytrap.

Common problems and how to solve them

What do I do if my Venus flytrap has white mold or fungus around it?

White mold or fungus is in some cases, saprophytic fungus, which is harmless. In other cases, it may be powdery mildew. This is more serious. Here are some remedies that we would recommend after figuring out which issue you are experiencing. Ensure your water level (in the tray method) is the appropriate height. Saprophytic fungi feed on dead plant and organism remains, since 80-90% of these fungi is made of water, they need water in order to exist. Dead plant material can also be caused by a partially rotting rhizome. If the water level in the tray method is too high around your venus flytrap, saprophytic fungi may appear. In the case of powdery mildew, some recommend fungicides or trimming, and pruning leaves. There are far too many treatments to list here but to name a few: a baking soda – soap – water mix (1 tablespoon of baking soda, 1/2 teaspoon of liquid soap [non-detergent], 1 gallon of water), or a milk and water mix (1 part milk to 2-3 parts water), lastly, you can use cinnamon as a natural fungicide. These remedies can range in efficacy on plants, and some remedies can be quite harsh on your plants. Please use these treatments sparingly, do the required research on antifungal remedies, and try to prevent these issues before they happen, namely with good ventilation and avoiding overwatering.

What do I do if my Venus flytrap is growing slowly?

If you find your Venus flytrap is growing slowly, you may try more light, as has been mentioned quite a bit in this guide. You may also try letting the tray dry out of water when using the tray method. Letting the tray dry out completely (just the tray, i.e. not letting the plant dry out). This can prevent fungi from growing in the root system and some growers even state that it makes the plant “reach” to chase the water, which it will do by growing its roots deeper in the ground and subsequently will allow it to grow larger (although there has been no scientific evidence we are aware of to confirm this explanation). Whatever the reason for this, the plants tend to grow best when the tray dries out before being refilled. As always, following our care guide closely can help grow your Venus flytrap quickly and in a healthy manner.

What should I do if my venus flytrap wasn’t watered and dried up?

Unfortunately, this problem is one of the most severe. Venus flytraps do not do well when they have dried up, especially when they are young or it has been a few days since the plant has had water. The best remedy is to rehydrate your plant by filling up the tray with water and top watering the plant. Some growers recommend uprooting and soaking the Venus flytrap for a short time (roughly a couple of hours maximum), to see if the rhizome of the plant is salvageable (still healthy white parts on it), and hydrated. It is very difficult to recover a plant that has been dried up because even with adding water, the probability of the rhizome rotting when moist is high as well. We recommend top watering as well as the tray method, thereby adding a little more water than usual. This will not completely shock the plant or expose it too much to rot conditions but will allow it ample moisture that it may soak up to recover.

What do I do if my Venus flytrap leaves are turning black?

What should you do if your venus flytrap is dying back? As mentioned above, black leaves are a natural part of the growing cycle of venus flytraps, you can cut them off (if you like) to avoid mold, bacteria, or pests from being attracted to your plants. A good sign that this is not anything to worry about is if the leaves dying off are the outer (older leaves) and if there is new growth coming up from the middle of the plant. It is also important to ensure that the rhizome of the plant is not 100% under the media to avoid it rotting away. Again, another culprit of black leaves is dormancy. Following the steps in the dormancy section of this guide should help with understanding what to do.

What do I do if my venus flytrap won’t close?

You can test the relative health of your Venus flytrap by triggering its traps and seeing how quickly they close. If the traps close somewhat quickly this typically means your Venus flytrap is healthy, if it closes slowly or not at all it may mean your Venus flytrap needs some improved environmental conditions or is experiencing a dormant period. Low light is a common reason for slow trap closing. Making sure your Venus flytrap has as much light as you can give it is a great way to improve its health. Putting the plant closer to a windowsill or even investing in some grow lights are proposed solutions to give your plant more light. It is advised that you try to use the above care requirements to make your venus flytrap as happy as possible! This will help it be its healthiest, and fastest! Another reason your venus flytrap might not close is that it is in a dormancy period. This is a natural cycle of the Venus flytrap as mentioned above. You can follow the instructions above for dormancy and wait for your plant to exit dormancy to start growing strong, fast closing traps again. This will give your plant much-needed rest and help it grow to its full potential.

Ensuring that the steps in the care guide are followed should help your Venus flytrap thrive!

Thank you for reading this article! We hope it was useful and will help your flytraps be the healthiest and most robust that they can be! We are constantly updating our website with new information and would love to hear any amendments, tips, tricks, or new information recommended by professional growers or scientific and peer-reviewed botanical literature. Happy growing, friends!